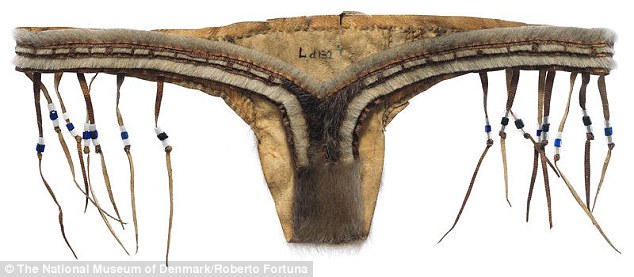

During the 19th century Inuits in Greenland would have entertained polite company in their settlements while wearing a thong made of seal fur.

Traditionally known as a ‘naatsit’, the underwear is adorned with beads and would have been sewn together by a woman using strips of seal pelt.

It is currently on display at the National Museum of Denmark in Copenhagen as part of its animal-skin clothing collection.

Traditionally known as a ‘naatsit’, the underwear (pictured) is adorned with beads and would have been sewn together by a woman, for a woman, using strips of seal pelt. It is currently on display at the National Museum of Denmark in Copenhagen as part of its animal-skin clothing collection

Peter Toft, the National Museum of Denmark‘s Greenlandic fur clothing expert, told Ella Morton at Atlas Obscura the underwear would have been worn inside the homes of the Inuit – even in front of guests or when visiting family members.

It was obtained during an expedition to the Ammassalik settlement in Greenland in 1892 by Captain C. Ryder.

When leaving the settlement, the female wearer would have worn it under trousers.

The naatsit was the only undergarment the Inuit would have worn next to their bare skin and it was often decorated with beads of glass, with the seal fur turned outside.

Example have also been decorated with small pieces of fur in different colours.

It was obtained during an expedition to the Ammassalik settlement in Greenland in 1892 by Captain C. Ryder. When leaving a settlement, the female wearer would have worn this naastit (pictured) under trousers

Seals are found along the coast of East Greenland and are hunted by Inuits (stock image) for their meat and skin. Seal fur provides less insulation than caribou fur to prevents the wearer from sweating and causing the material to become damp, and later freeze in the cold

Cunera Buijs from the National Museum of Ethnology said: ‘When weather conditions permitted, the naatsit was often the only garment worn, both in the home and outside in the settlement.‘

These homes would have been built to keep in the heat, with a low corridor entrance positioned in such a way to cause warm air to rise from beneath the structure into the home, and stay there.

In addition to the naatsit, the National Museum of Denmark’s collection also features a diaper made from reindeer fur (pictured)

Many of these primitive buildings would have housed more than one family.

‘There does seem to have been a taboo against walking around outside the home only in shorts,’ continued Ms Buijs.

‘As soon as the Inuit men left their own settlement, they put on a pair of long trousers made of seal or polar-bear fur.’

Seals are found along the coast of East Greenland and are hunted for their meat and skin.

Inuits across the region, and into North America and Siberia, would have also made garments from the skin and fur of reindeer and caribou.

The severe conditions of the region means that clothes have to protect against the cold, wind and damp and seal fur, in particular, provides less insulation than caribou fur.

This prevents the wearer from sweating and causing the material to become damp, and later freeze in the cold, continued Mr Toft.

Women would clean the skin and remove all traces of flesh to prevent them from rotting, a pricess called ‘flensing’.

The fat would be scraped away on a board called a qapiarpik and the clothing would have been sewn together using a sakkeq or ulu – a traditional woman’s knife – and a needle.

The display also contains a pair of pantyhose made from reindeer skin and fur (pictured). A similar collection is on display at the National Museum of Ethnology, which came via the museum in Copenhagen

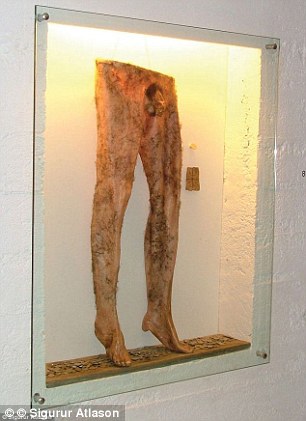

THE 17TH CENTURY NECROPANTS MADE FROM HUMAN SKIN

In 17th century Iceland, sorcerers wore ‘trousers’ made of a dead friend’s skin that were said to bring them wealth (example pictured)

In 17th century Iceland, sorcerers wore ‘trousers’ made of a dead friend’s skin that were said to bring them wealth.

According to legend, a morbid deal was struck between two friends to arrange who became the trousers or ‘necropants,’ which were used for purposes of traditional magic at the time.

The Museum of Icelandic Sorcery & Witchcraft in Holmavik, Iceland, houses the only known intact pair of necropants, that were meant to be worn day and night by their owner.

In order to make the necropants (called nábrók in the naive tongue) an individual had to get permission from a living man to use his skin after his death.

The surviving member of the pact had to dig up his dead friend’s body and peel off the skin of the corpse from the waist down in one piece without any holes or scratches, to make the magical trousers.

As soon as they stepped into the pants, the skin of the corpse stuck to theirs own, according to the museum, which documents 17th century occult practices.

To make the grim garment, the wearer of the pants had to steal a coin from a poor widow at Christmas, Easter or Whitson and place it in the scrotum of the trousers, along with the magical sign called nábrókarstafur, which is drawn on a piece of paper.

The coin is a ‘tool to gather wealth by supernatural means,’ according to the spokesman.

It drew money into the scrotum from living people so ‘it will never be empty’ as long as the original coin is not removed, according to folklore.