The basic design of commercial airplanes hasn’t changed much in the past 60 years. Modern airliners like the Boeing 787 and the Airbus A350 have the same general shape as the Boeing 707 and the Douglas DC-8, which were built in the late 1950s and solidified the “tube and wing” form factor that is still in use today.

This is because commercial aviation prioritizes safety, favoring tried-and-tested solutions, and because other developments — in materials and engines, for example — mean the traditional design is still relevant.

However, as the industry desperately looks for ways to reduce carbon emissions, it faces a somewhat tougher challenge than other sectors precisely because its core technologies have proven so hard to move away from. The time might be ripe to try something new.

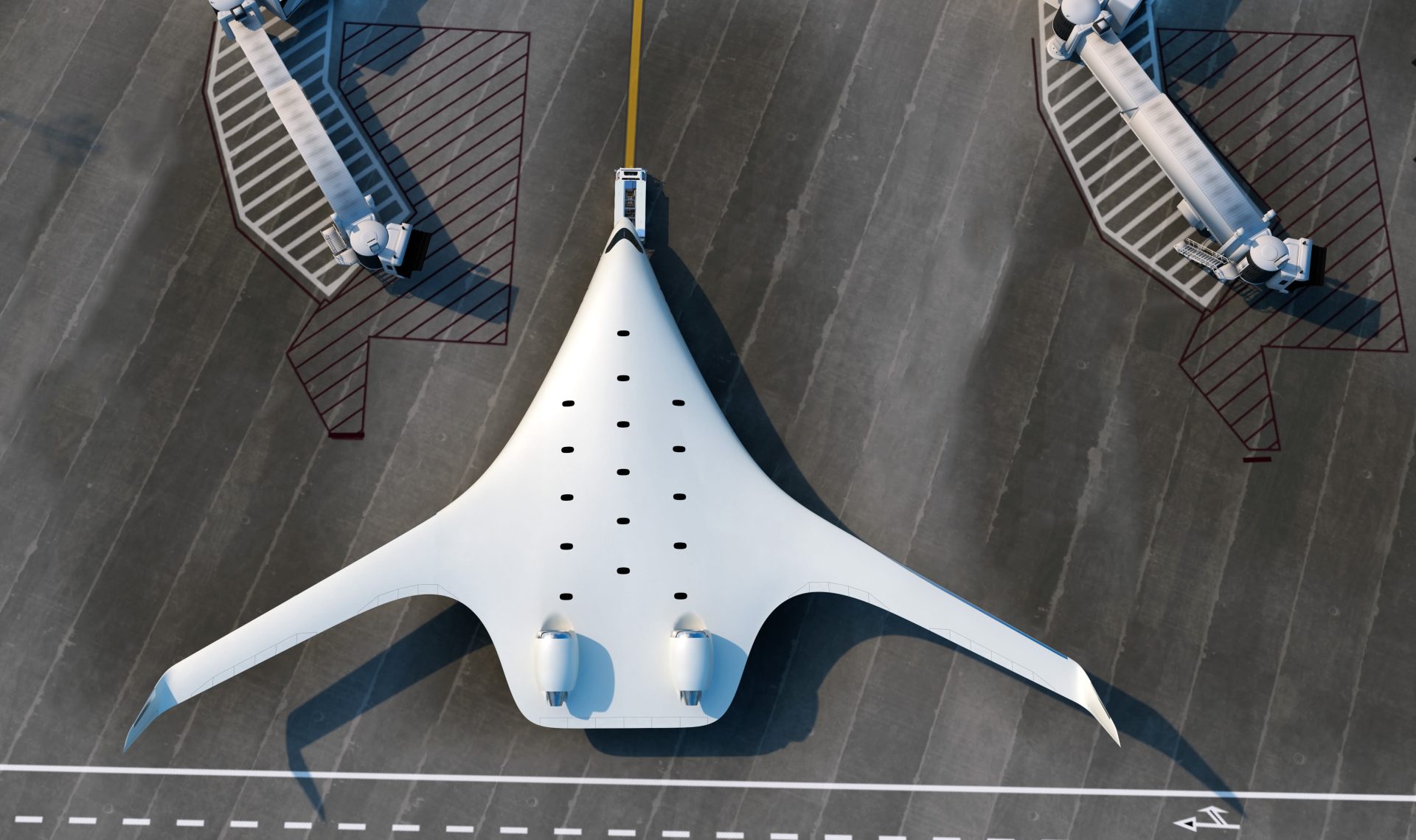

One proposal is the “blended wing body.” This entirely new aircraft shape looks similar to the “flying wing” design used by military aircraft such as the iconic B-2 bomber, but the blended wing has more volume in the middle section. Both Boeing and Airbus are tinkering with the idea, and so is a third player, California-based JetZero, which has set an ambitious goal of putting into service a blended wing aircraft as soon as 2030.

“We feel very strongly about a path to zero emissions in big jets, and the blended wing airframe can deliver 50% lower fuel burn and emissions,” says Tom O’Leary, co-founder and CEO of JetZero. “That is a staggering leap forward in comparison to what the industry is used to.”

In 2020, Airbus built a small blended wing demonstrator, about six feet in length, signaling interest in pursuing a full-size aircraft in the future. But if the shape is so effective, why haven’t we yet moved to building planes based on it?

According to O’Leary, there is one main technical challenge holding manufacturers back. “It’s the pressurization of a non-cylindrical fuselage,” he says, pointing to the fact that a tube-shaped plane is better able to handle the constant expansion and contraction cycles that come with each flight.

“If you think about a ‘tube and wing,’ it separates the loads — you have the pressurization load on the tube, and the bending loads on the wings. But a blended wing essentially blends those together. Only now can we do that with composite materials that are both light and strong.”

Such a radically new shape would make the interior of the plane look and feel wildly different to today’s widebody aircraft. “It’s just a much, much wider fuselage,” O’Leary says. “Your typical single-aisle plane has three by three seats, but this is a sort of a shorter, wider tube. You get the same amount of people, but you might have 15 or 20 rows across the cabin, depending upon how each particular airline will configure it.

“This just gives them a whole new palette with which to lay it out. I think it’s going to be amazing to see what their interpretation of this much broader space will be.”